Master Innovation

Prototyping: The design process to pressure-test ideas

Pressure-test your design process with these simple steps

July 11, 2018

No great idea is born in a vacuum. For two reasons:

- The elements that make up a great idea are not always visible from the start.

- New great ideas come to life when they collide and mix with existing ideas.

Great ideas are also not formed in a single spark of isolated genius. In his TED talk, Steven Johnson describes how the theory of natural selection was outlined in Darwin’s notebooks months before the moment Darwin reports having his ‘eureka’ moment of clarity. Even though there were hints in plain sight all along, the full idea needed time and commixing with other thinking to finally clearly emerge.

A key tool in design thinking is prototyping to develop new and meaningful ideas with early testing and experimentation. IDEO founders, Tom and David Kelley, describe why prototyping is so helpful:

"The act of creating forces you to ask questions and make choices. It also gives you something you can show to and talk about with other people."

Nathalie Collins, senior lead designer at IDEO.org, describes prototyping as “a way to think” where something is brought “from a place of theory to a place of tangibility.” By taking the approach of frequent testing, gathering feedback, and iterative learning, your idea follows a trajectory of continuous improvement until it has ‘succeeded’ (or generates value in a predictable and repeatable fashion).

How prototypes evolve through the development of an idea

There is a saying in design thinking:

First you want to design the right thing, then design the thing right.

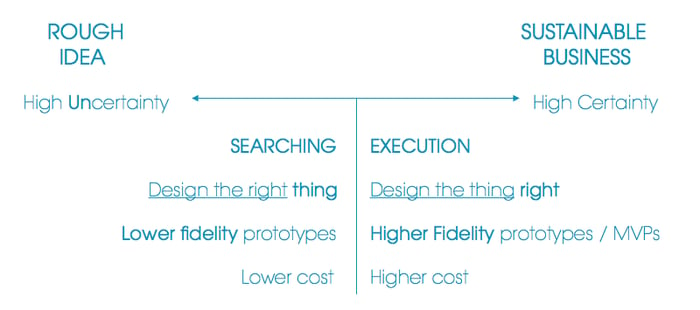

Alex Osterwalder of Strategyzer frames the process of developing a rough idea into a sustainable business using a spectrum like the one below.

Alex Iskold describes the difference as: “an MVP is good enough, and can be improved to be great one day. Prototype isn’t good enough.” This means a prototype is useful for testing specific questions as the product or service is being developed, but an MVP should be sophisticated enough to deliver on its promise of value. After all, this usefulness is what makes it viable.

Prototypes are the tools to help you prove a concept and MVP’s help you refine it.

The process for developing fail-proof ideas with prototyping

Step #1 - Determine what to prototype

IDEO suggests starting by writing down all of the elements of your idea. For each, list the questions you have. In a similar way, Strategyzer recommends making a list of all of your assumptions, which are the statements that need to be true in order for this idea to deliver the results you envision.

Consider which questions and assumptions are the most crucial for your idea to work and keep these in mind as you build your first prototypes.

- Start by testing hypotheses that have to do with the problems (pains), activities (jobs) or goals (gains) the potential customer faces.

- Only after you have a good understanding of their perspective should you move onto validating the solution itself. In other words, confirming the solution (product or service) you have in mind will deliver value that is meaningful and desirable to your customers.

- When the best solution to serve your customers is clear, the final phase of questions to explore is around how you will do it.

- Keep it simple: focus on one element of your idea at a time.

- Ask one question at a time: each test will provide information to add to the big picture, and your prototypes will get more sophisticated over time to incorporate all the learning.

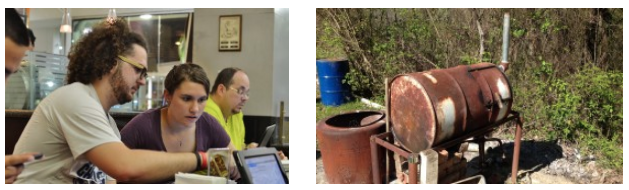

- It needed to be made from local materials only (i.e. no soldering metal)

- It needed to be ergonomic and comfortable to use

- It needed to emit little to no smoke

- It needed to collect the most cashew oil possible

- The costs needed to be under $100

The students built and tested several versions before arriving at a stove design that extracted 12% of the oil (out of available 15%), up from only 1-3% collected from the first prototype. By designing with constraints they were able to focus their prototyping process to address the most important areas. The new stoves were expected to minimize respiratory health issues and help increase villagers’ household income by 10-20%.

Step #2 - Make it real

Close

Step #3 - Get feedback

With a mock-up prototype in hand, the team conducted several interviews to gain feedback from the end users. From this process, they learned that privacy and security were a key concern for refugees. As helpful as RFID technology was for connecting into Stockholm infrastructure, for refugees concerned with privacy, carrying a card that made their exact location known to the service providers made them uneasy. Learning this information early in the design process saved the team countless hours and resources that might have been spent developing out a flawed solution.

Step #4 - Iterate & repeat

Prototyping techniques

- Storyboard: a visual representation of a sequence of events or interactions. Rough sketches on sticky notes works perfectly to show what someone might be feeling, doing, or seeing. IDEO suggests brainstorming multiple options for each stage in the sequence on extra sticky notes so more variations of the storyboard can be easily visualized.

- Role play: act out a customer/user scenario in person to test how your idea would work in action.

- Bodystorm: a mix of role playing and brainstorming to use empathy to come up with new ideas.

- Game / simulation: set up a game where users can interact with an idea; great for observing how people act in various contexts.

- Make a physical survey: another idea from IDEO is to make a question tangible using a yes or no jar where people passing by can place their vote.

- Concept art: an illustration of your idea to show to potential users to gather their first impressions and questions.

- Non-working model: a 3D representation of a physical product using readily available materials without functionality; used to get a general idea of size and form.

- Working model: a 3D representation of a physical product (using readily available materials) that has functionality similar to the end product.

- Wireframe: a series of simple 2D sketches to show the main elements of an idea and how they fit together; often used to map out the components of an app or website in early stages.

- Mock-up: a 2D design that looks finished but lacks full-functionality (like simulating clicking through a website).

- Video / film: to act out or describe and show the idea in action.

- If you need more inspiration, here’s another list of prototype examples.

Watch Now

Close

Author

Danielle Sutton

Danielle Sutton is the Content Animator at Acumen where she surfaces stories to inspire and activate social entrepreneurs. In an age of information overload, she believes in learning 'the right thing at the right time' to intentionally design impactful social enterprises. You can usually find Danielle digging into the Acumen course library, playing in the mountains, or exploring marketing on The Sedge blog.