Leadership

Social entrepreneurship: What it is and how to use it for change

Discover how 14+ social entrepreneurs and their organizations are shaping a new chapter in social change through moral leadership.

41 minutes

Ask any young person today who is passionate about social change and you can’t deny that the discipline of social entrepreneurship has taken root in our society. However, there is a missing element in the global conversation about what it means to be a social entrepreneur: the practice of Moral Leadership.

The rise of social entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurship was sparked by those who realized that traditional capitalism was failing our most vulnerable, and decided that inequity and injustice could no longer be ignored. Boldly, they asked, ‘What is possible when we position people and the planet at the forefront of our decision-making?’

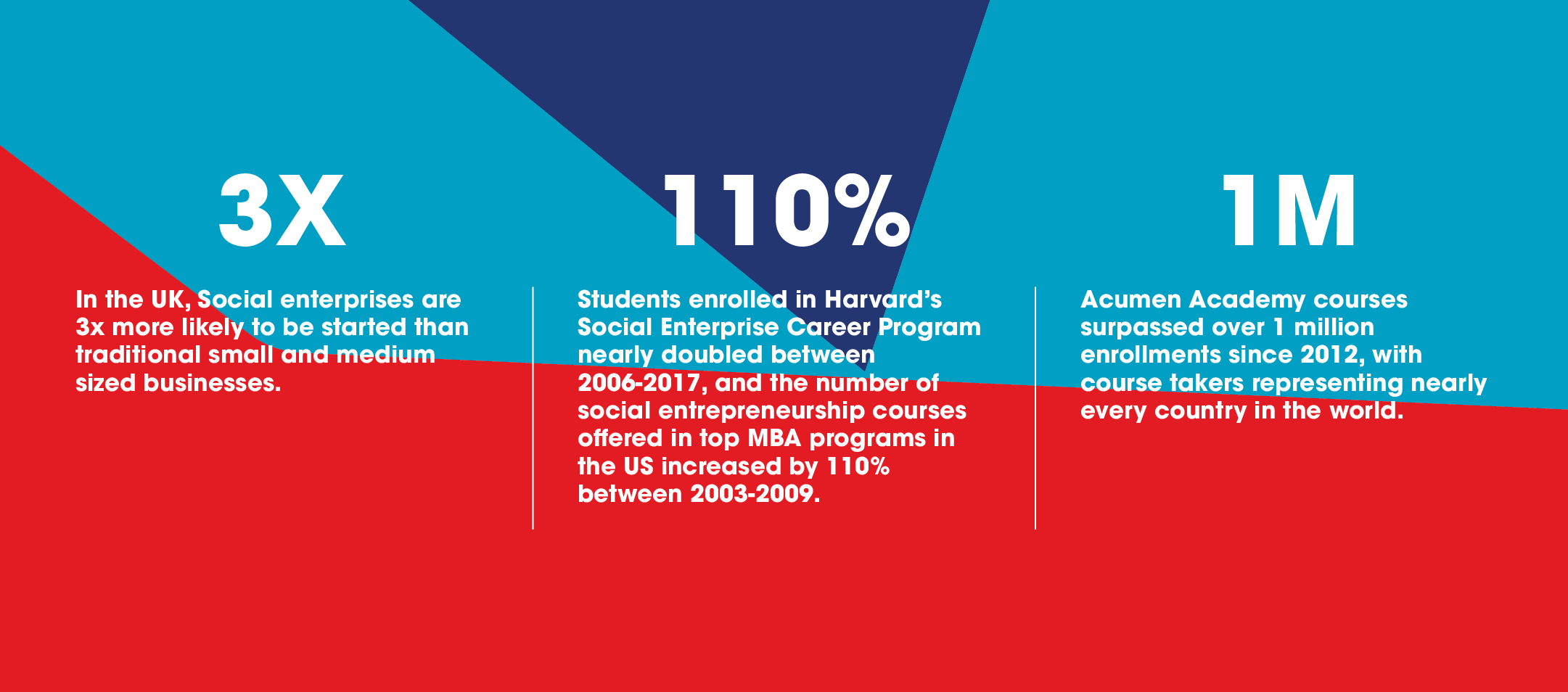

The energy around the need for and growth of social entrepreneurship is undeniable.

India Fellow

Ashish Shrivastava

Ashish is the Founder of Shiksharth working in conflict affected tribal India in the state of Chhattisgarh. Shiksharth is a not-for profit educational research initiative focusing on education in rural and tribal India. Currently working towards engaging community and parents actively in excellent learning for their children by introducing contextual...

However, in the excitement of building scalable, innovative, customer-driven solutions, a crucial component has been lost: sustainable social enterprises require both a mastery of the business fundamentals and the practice of moral leadership.

What differentiates social entrepreneurship from traditional business

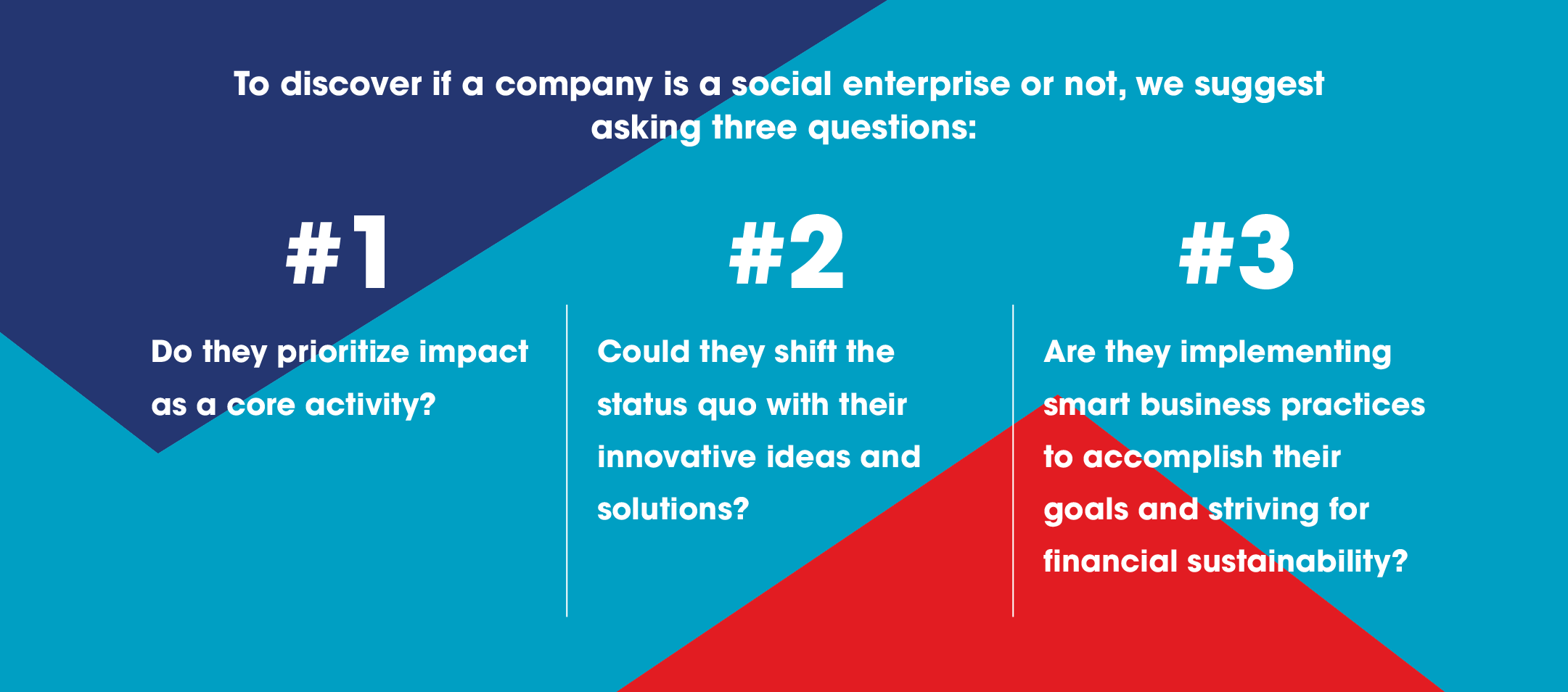

A social enterprise is defined as any organization that prioritizes transformative social impact while striving for financial sustainability.

In a perfect world, there won’t be a need to distinguish between ‘businesses that do good’ and ‘business that make money.’ Until then, defining what makes a social enterprise unique is worth understanding.

- Is a social enterprise a nonprofit that acts like a business?

- Is social enterprise a business with a triple bottom line?

- Can a business serving the environment be a social enterprise?

- Can a social enterprise earn a profit?

- Does a social enterprise need to be a nonprofit entity or a for-profit entity?

We bring this up because there are several examples of organizations some might consider as social enterprises but that don’t necessarily prioritize impact as a core function of their operations. For example, a company like Warby Parker is commendable in making the eyeglasses industry more affordable, using smart business practices to manufacture and distribute eyeglasses at a reasonable price, and donating over five million eyeglasses to low-income customers through their buy a pair, give a pair partnership with VisionSpring. However, Warby Parker could stop donating glasses tomorrow and its core business would not change.

How to shift the status quo with social entrepreneurship

Magic happens when social entrepreneurs find the sweet spot where they generate value for the people they aim to serve, package that value in a way that people are willing to pay for, and do both in a way where each drives the other in a virtuous cycle. With every step toward a new, more fair system, the revenue model is fueled, and vice versa.

Finding this social innovation sweet spot is not easy, but there is a common theme shared by experienced social entrepreneurs that provides a big head start: imagining solutions that haven’t been tried before requires falling in love with the problem you aim to solve, not with the idea you think will solve it.

Social entrepreneurship finds overlooked power in low income communities and then changes the system to tap that power.

JB Schramm

Co-Founder of College Summit

Why we need a socially-conscious approach to business

Without moral leadership, entrepreneurial strategies, tactics, and business models in pursuit of social aims risk being superficial band-aids. The principles of moral leadership give these efforts soul.

A more just, inclusive, sustainable world

What makes a social entrepreneur

While famous examples like Muhammad Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize winner and founder of Grameen Bank, come to mind when thinking of social entrepreneurs, any person with a passion and commitment for creating change can be a social entrepreneur.

Common characteristics of social entrepreneurs

Comfort navigating uncertainty

Social entrepreneurs are flexible to adjust course as needed when new context or circumstances come to light. They embrace uncertainty as an indication of wide-open possibility.

Resilience

Social entrepreneurs view every failure as new information to inform the next decision. Running into setbacks does not stop them in their tracks but instead provides fuel to double-down and try again.

Grit

Social entrepreneurs are frequently told to never give up, even when they encounter rough patches. Acumen’s own manifesto reminds us that tackling problems of poverty “requires patience and kindness, resilience and grit: a hard-edged hope.” Want to grow skill? Acumen Academy’s Master Class instructor, Angela Duckworth, teaches practical steps to build grit.

Commitment to impact

Social entrepreneurs are committed to the problem they wish to solve but are flexible in how they achieve it. They always prioritize impact outcomes over commercial or financial measures of success.

Creativity

Social entrepreneurs don’t let their thinking be limited by what’s been done before. They seek overlaps across diverse disciplines and sectors to see new, often surprising, ways to create, capture, and deliver value.

Courage

Social entrepreneurs are courageous to stand up for what they believe and take action that sometimes goes against the grain.

Willingness to lead

Social entrepreneurs embrace leadership challenges, large and small. Even when they don’t formally lead a team, they recognize leadership moments when they may need to make tough decisions, or speak up even if it’s unpopular or uncomfortable.

Humility

Social entrepreneurs recognize they do not have all the answers. They are quick to listen and slow to jump to conclusions.

What the practice or moral leadership looks like when it hits the ground

The practices of moral leadership are just that – practices. Each is an exercise to be undertaken over time. Manifesto for a Moral Revolution explores each of the 12 practices in detail, but for the purposes of this guide, we grouped them into four categories:

1. Redefine success with moral imagination

Close

Unequal systems persist, yet they can be reimagined and reformed when people muster enough awareness and collective determination to do something about them.

Jacqueline Novogratz

Founder & CEO, Acumen

2. Build inclusive organizations

Close

3. Connect across lines of difference

Close

While our connected world exposes divisions across ideologies, values, and priorities, it also yields a richness in the sheer volume of perspectives to learn and grow from.

One way to connect across lines of difference is to use the power of story. Storytelling is a non-negotiable skill for any social entrepreneur because stories give voice to the arguments that drive decisions and to the thoughts that drive action. Nothing is more powerful for shifting the status quo than speaking to mobilize people toward a shared vision for change.

How intentional relationships help green face trading grow beekeepers and business

Green Face Trading started as a one-man operation and, in only two years, grew into an international supplier of organic and sustainable honey that aims to further conservation efforts. Acumen Academy Accelerator participant, and Founder and General Manager Jony Girma, credits much of his success to building meaningful connections.

When bringing his business to new villages across Ethiopia, Jony takes time to set up learning centers and meet the community. He is personally invested, explaining, “I am from a rural area, so I understand, and I know how challenging and painful being unemployed is. That's why I'm really happy to create jobs and work with villages.”

Jony sits down with the local youth to talk about their employment challenges, and how by working to conserve natural resources together, they can create more job opportunities for themselves and their peers. Early adopters who join Green Face Trading end up serving as ambassadors, spreading their success and knowledge through word of mouth. He is proud to see how youth succeed, explaining that one of his high school self-employed beekeepers covers, “all his school fees and books from the honey sales.”

“Being inside the community helps you to understand the problem, and easily follow and develop strategies to solve the problems.”

During the beekeeper training process, building connection and bridging identities remain central for Green Face Trading. Not only do they support technical training, they also weave in motivational training by bringing in local elders. “We ask older people to compare their living, the forest coverage of the area, and the impact of deforestation to their livelihood, income, and health … This creates an opportunity for this generation and the youth to understand the impact of deforestation.”

It’s important to Jony that Green Face Trading doesn’t have a traditional business relationship with the beekeepers. When he visits local villages, it’s often in people’s homes, sharing tea and listening to their stories. “This all helps me to develop a family connection with them … I feel like I'm going to visit my own family.”

Maintaining close relationships with his beekeepers also proves to be good for business. “If they get poor quality honey, they're not going to sell to me,” Jony explained. And having familial relationships makes it easier to give and receive feedback that improves the business. “Every time we discuss, they are open and tell me what to do for them to improve productivity and to improve the quality [of honey].”

Based on their interactions, the beekeepers also advise Green Face Trading about trustworthiness and reliability of potential supply chain partners. Jony explained that opening up these paths of communication has, “helped me to improve my supply chain because of the feedback I have from them.” By accompanying the beekeepers and valuing their input, Green Face Trading has created a culture in which beekeepers also serve as the eyes and ears of the company with it’s best interest in mind.

"Listen, and try to really build relationships and strong networks into the business."

Accompaniment, building meaningful connections, and listening have proved monumental for Green Face Trading’s growth. Jony believes these are the key hard-edged skills needed for any entrepreneur. “When I'm talking with the beekeepers or with buyers, I listen to everything and … I try to find a solution for their problems. Especially when we're working with our rural communities,” Jony explained, “there should be a good partnership — a good relationship beyond the business — like a family relationship.”

His success with building relationships extends beyond his beekeepers, too. “This principle is not only with our community, it’s even with my buyers … because of this approach, my buyers pay me advance payment, so this helps me to develop my business.”

By building genuine relationships, accompanying all stakeholders across his organic honey ecosystem, and bridging identities, Green Face Trading continues to foster a trustworthy and thriving business.

4. Persist in the beautiful struggle

Close

HOW UZURI K&Y REDUCES WASTE AND CREATES OPPORTUNITY - FASHIONABLY

While in college at University of Rwanda, Acumen Academy Accelerator participant Kevine Kagirimpundu realized that there are very few job opportunities available upon graduation. That means even fewer opportunities for those without a degree.

In 2017, unemployed youth — including Kevine and her university classmates — made up 60% of Africa’s unemployed population. On top of the staggering unemployment rate, the local environment was also suffering. Kevine was appalled to see discarded tires — that serve as breeding pools for mosquitos and emit water and air pollutants — becoming more prevalent in her community.

Eager to create change for the local economy and the environment, Kevine teamed up with her business partner, Ysolde Shimwe, to launch UZURI K&Y.

“If I can't be employed, and I'm one of the top students in my class, and I'm one of the few girls in school, can you imagine someone who doesn't have such an opportunity?”

UZURI K&Y is an African-inspired eco-friendly footwear brand that recycles waste — like old tires — into fashionable and functionable shoes. Initially, peers tried to dissuade her from starting the company, believing that fashion wasn’t an economic priority. But that didn’t stop Kevine and Ysolde. They remained ambitious and resilient, not letting naysayers get them down. “Creating job opportunities really was a huge driver for me — to create jobs for myself and other people like myself,” explained Kevine.

Despite being without skilled labor, business insight, and sufficient raw materials and funds, the two put out an ad over the local radio. Hoping to get 50 applicants, they ended up with over 300. This validated the need for employment, but it also posed a problem — how could they help those they couldn’t afford to employ?

Thinking fast, the two decided to pivot and launch a training program to teach excited community members technical and design skills. They partnered with German organization, Senior Expert Services, to provide attendees with the soft skills needed to help them navigate the job market — even if it meant leaving to start their own business. In fact, UZURI K&Y encouraged it.

With creating employment opportunities at its core, UZURI K&Y’s emphasis on professional empowerment triggered unintended benefits. One of their former employees, Eda, left the company to start her own successful footwear business. Now, trainees of UZURI K&Y’s program visit Eda’s workshop to learn from her, creating a cycle of support, training, and empowerment. “She has become a success story to tell in my trainings everywhere. She has done an incredible job … and she's also playing as a role model for other young people, especially young women,” beamed Kevine.

“We grew from one table working with one employee to now having a whole team of over 85 people. But it started from the idea of just a hungry young woman trying to create change in her own community.”

Since 2013, UZURI K&Y has impacted the careers of over 1,060 people — 70% of which are women — and have helped 10 former employees launch their own businesses. By persisting in the face of critics, trusting their intuition, and building a truly impactful enterprise that promotes an eco-friendly, sustainable, and community-centered mission, UZURI K&Y has redefined how a business can create change.

Prepare to start a social enterprise

If you have an idea for a social enterprise but haven’t yet started, what’s stopping you?

Is it because you’re not sure what the first step is or that you'll make a mistake? Is it because you feel you need more planning before starting?

Some people sit on an idea for years and never take the leap to ‘just start.’

Reframe your mindset

If you feel overwhelmed, it also helps to break down your goals into smaller steps. It’s much easier to complete small actions, and once you do, you’ll gain added clarity and momentum to keep going.

Get out of the building

Come up with a social enterprise idea

Watch below: How to identify a problem to solve

Close

Define success on your own terms

How to build an inclusive social enterprise

The goals of a social enterprise need to go beyond delivering a good to make money or maximize shareholder value. The very design of the organization and the decisions made by leadership need to embody the values of social entrepreneurship.

Inclusive social enterprises start with the customer, use innovative business models to deliver value in unique ways, and use markets for good while keeping them in check.

We miss many opportunities by assuming we have the answers.

Jacqueline Novogratz

Founder & CEO, Acumen

Co-create with your customers

Design innovative business models

Sales, fee-for-service, or earned income

This social enterprise business model is perhaps the simplest and what we’re most familiar with. An organization packages their products and services and sells them directly to customers who are willing to pay because it fulfills an unmet need in the marketplace. One example is Acumen investee, Burn Manufacturing.

Microfranchising

In this model, an organization offers community members an opportunity to license and run a “business in a box”. These new entrepreneurs are supported with infrastructure, capital, and inventory to get their business off the ground. Revenue is generated through a percentage of the franchisee’s sales. One example is VisionSpring.

Cross-subsidization

This model has one set of customers paying a higher rate for the same product or service provided to all customers. This allows the segment of customers with less ability to pay to receive the goods for free or at a highly subsidized rate. An example of this model is Aravind Eye Care System.

Market linkage

Social enterprises with this business model connect entrepreneurs to marketplaces. It could be via the purchase of their products at market rates and then reselling to international markets at a higher price point. This allows the social enterprise to earn a profit while providing the entrepreneurs they purchase from to benefit from a steady stream of sales. Another option is for the social enterprise to provide a value-add service to the entrepreneurs, such as marketing, technical assistance, or financing, to support their reaching new markets. One example of this type of social enterprise is One Acre Fund.

Microphilanthropy

This model, made popular by organizations like Kiva, uses crowdfunding strategies to pool smaller amounts of money from several contributors. The business costs are covered via donations from crowdfunders or built in fees to use the platform.

Employment generation

This model provides employment for populations who may face opportunity barriers or require additional support, like the social enterprise Samasource. Employees are the beneficiaries of the social enterprise, and are a core contributor to the organization by way of the creation or delivery of the enterprise’s products and services.

Use markets for good

Partner with humility and audacity

India Fellow

Vivek Kumar

Vivek is Co-founder and CEO of Kshamtalaya Foundation, an organization supporting communities to revive the spirit of learning in and outside of schools. Core to the organization’s program is a curriculum that provides space for self-directed learning, systems thinking, and mindfulness. Its learning manifesto and learning festivals aim to make education...

HOW BRIO OFFERS AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO MENTAL HEALTH

In order to truly help communities, we need to meet them where they are. But how do we adapt programs with a high barrier to entry — like mental health care — and make them more inclusive, accessible, and community-centered?

After seeing the power and trust harnessed by local organizations, Brio co-founders and Acumen Academy accelerator participants, Daisy and Aaron Rosales, knew the best way to create change and break down mental health barriers would be to accompany these communities rather than provide prescriptive answers.

The journey toward inclusive accompaniment began when Daisy and Aaron were volunteering in Quito, Ecuador. They were aware of the high rate of domestic violence and its close relationship to alcohol use — in fact, they later found that 98% of the families they served reported incidents of alcohol-related domestic violence.

Knowing that survivors often stay silent about the abuse, Daisy was shocked to find one of the women opening up about her experience after only a few weeks. “Building that trust was a sign that, when it comes to thinking about mental healthcare and working with communities to develop effective models, the local organization — those spaces that people trust —are going to be really important.”

Building partnership models is not the norm for mental health support — and it definitely isn’t the easy route. In order to adequately support communities, Daisy and Aaron felt it was important to accompany existing local, trustworthy organizations. With Aaron’s PhD in Clinical Psychology and Daisy’s background supporting social movements and addiction care, the two launched Brio. Brio set out to provide quality mental health care in low-resource communities through their partnership and toolkit model, starting in Ecuador. Brio equips local human service organizations with the tools needed to provide effective, sustainable care.

“We’re not in the business of going to communities and saying, ‘we believe that half the people here are depressed, so we’re here to offer you a solution for depression.’” - Daisy Rosales

Building a model that partners with local organizations helps overcome additional barriers, too. Although government mental health programs exist in regions where Brio works, some are in foreign languages, rendering them useless. The cost for support and supply of trained professionals — especially in Latin America — isn’t practical nor sustainable. And the stigma around mental health and its prescriptive, scientific language can be daunting to community members. Through a partnership model, Daisy and Aaron address these issues by creating affordable, community-centric programs with attention and sensitivity to language and message.

In 2018, Brio launched their community-owned approach — with accompaniment and people at its core. By listening to local community members and empathizing with their pain, Brio partners with organizations to design solutions that address specific community needs.

“We don’t just offer skill-building or just consultant work, but it’s more about the way we relate, the way we show up, the way we work alongside our partners that is really essential.” - Aaron Rosales

Brio accompanies local leaders — from Mexico to India — and empowers them to build and scale their mental health programs. After discussing community pain points, Brio provides leaders with the tools needed to take action, evaluate, and iterate. “Essentially, what they end up with is a highly responsive program that they’re able to administer and train others in that is specifically designed for the problems that they see,” Daisy explains. Ultimately, Brio’s goal is to build a network where local leaders and organizations can share successful and effective models with communities impacted by similar problems.

Brio also provides free access to a library of resources. In August 2020, Brio launched their Mental Health Design Toolkit, sharing the same processes, research, and design-thinking brought to community partnerships. As Brio grows, they plan to continue analyzing impact in the communities they work with to ensure shared tools remain relevant and helpful.

By listening empathically to the communities they set out to serve, creating meaningful partnerships, and building a bold and inclusive business structure, Brio is redefining how we can better serve communities in need.

How to lead a social enterprise

Even the most well-laid plans will run into obstacles. Leading a social enterprise requires grit, resilience, perseverance and adaptability.

There will be times when progress moves quickly, when plans get executed as expected, and the organization seamlessly hits the next major milestone. But there will also be moments that make the leadership team wonder if they’re doing the right thing: funding will fall through, suppliers will delay production, staff will need extra attention.

But social entrepreneurs are committed to the long-term vision of what’s possible. They call in courage to navigate values in tension and to have difficult conversations. They tap into their community to help guide them. And they remain focused on the metrics that matter and persevere to carve out new norms and show others new visions are possible.

Embrace leadership moments

Video: Getting on the balcony with Erin Martin

Close

Have courageous conversations

Join like-minded community

Measure what matters

- Who are you serving?

- What changes are happening in their lives? Are the changes positive?

- How much are lives changing?

- How many people are you reaching?

Persevere through failure

East Africa Fellow

Abubaker Musuuza

Abu is the Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Village Energy Limited a social enterprise that is building a network of rural solar shops that deliver quality products and ensure effective access to skilled solar technicians, repairs and solar parts. Village Energy runs a rural solar academy that is training youth in technical and entrepreneurship ...

Considering this level of impact is possible thanks to one entrepreneur’s perseverance through failure, imagine the possible collective impact of every entrepreneur who refuses to give up.

Got a specific social issue or challenge that you want to focus on tackling? FREE course Start Your Social Change Journey will help you take the first steps to sustain your social impact efforts and keep your goals on track.

Hear four Acumen Academy social innovators share their thoughts on social entrepreneurship and the role of moral leadership:

Close

Embrace the Principles of Moral Leadership to Build a Better World

Receive 12 mini-lessons and accompaniment activities sent to your inbox.

Discover more

Sign up to our newsletter

I have read and accept the Terms & Privacy