Master Innovation

Transforming a fishing community in Mexico through systems thinking

Liliana Gutierrez, Executive Director of Noroeste Sustentable (NOS) shares how one fishing village set out to restore a declining clam population and ended up restoring the entire community in the process.

September 03, 2018

A vicious cycle of depleted fisheries and limited economic opportunities

In 2011, the nonprofit Noroeste Sustenable (NOS) began working in El Manglito in La Paz, Mexico. Off the coast, the scallop and clam fishery of the Ensenada de La Paz had been devastated. The local community relied on fishing as their sole source of economic livelihood and was therefore becoming desperate as fishing stocks declined. They turned to crimes, drugs, and illegal fishing as they tried to make ends meet.

NOS was a small NGO, but it was determined to revitalize the local marine ecosystem. The organization optimistically set up a new office in one of the poorer areas of the community, but quickly encountered longstanding distrust between the local fisherman and environmental conservation groups. The community viewed conservationists as a threat because they often sought to limit local fishing--and therefore take away their jobs.

However, NOS knew they had to prevent people from fishing illegally in the marine-protected area if they wanted to address the declining pen shell clam population and restore the local fisheries and lagoon. To do so, NOS began a citizen’s initiative to patrol the ocean to find illegal fisherman. Quickly, however, the organization realized that there really were no “bad guys” in this situation. The reality was much more complex.

The executive director of NOS, Liliana Gutierrez, describes one conversation she had with two local fisherman who had been caught fishing illegally--and how it began to make her realize this conservation challenge would have to be tackled at a much broader level: “Here I am talking with these two men who are explaining that all my preconceived ideas about illegal fishing were wrong. Their situation wasn't easy either. We began having very human conversations, and we began to understand each other's sides of the system.”

This interaction illuminated the interdependencies within the La Paz fishing ecosystem. As NOS spent more time with the community, they came to better understand the root causes that led to overfishing. Here’s what was happening:

- Local fishermen relied on bringing in a daily fish catch to support their families. They had few other sources of economic opportunity in the community.

- Additionally, many young people were dropping out of school to become fishermen because that seemed like the more immediately lucrative opportunity for them.

- As fishermen depleted or exhausted fishery sources near their villages, they began moving further and further out to access more fish.

- Fishermen found themselves incurring higher fuel costs from since they had to drive their boats further.

- Therefore, they need to haul in bigger catches to recover their expenses.

- Over time, fewer people in the community were educated because they dropped out of school to fish, and this in turn put more pressure on fish resources, and also meant that fewer people had the degrees and qualifications to pursue other jobs.

- This caused the vicious cycle of limited job opportunities and depleted fish populations to continue, eventually leading the local fishery to become severely depleted and put the ocean’s biodiversity at risk.

- Simultaneously, crime and drugs were on the rise as the population became more desperate for alternate sources of income, and had more idle time.

Clearly, this was a complicated situation that needed to be handled carefully. If conservationists somehow managed to restore the fishery but did not successfully involve the fishermen or help them find other sustainable livelihoods, the vicious cycle would continue and any environmental progress would erode quickly.

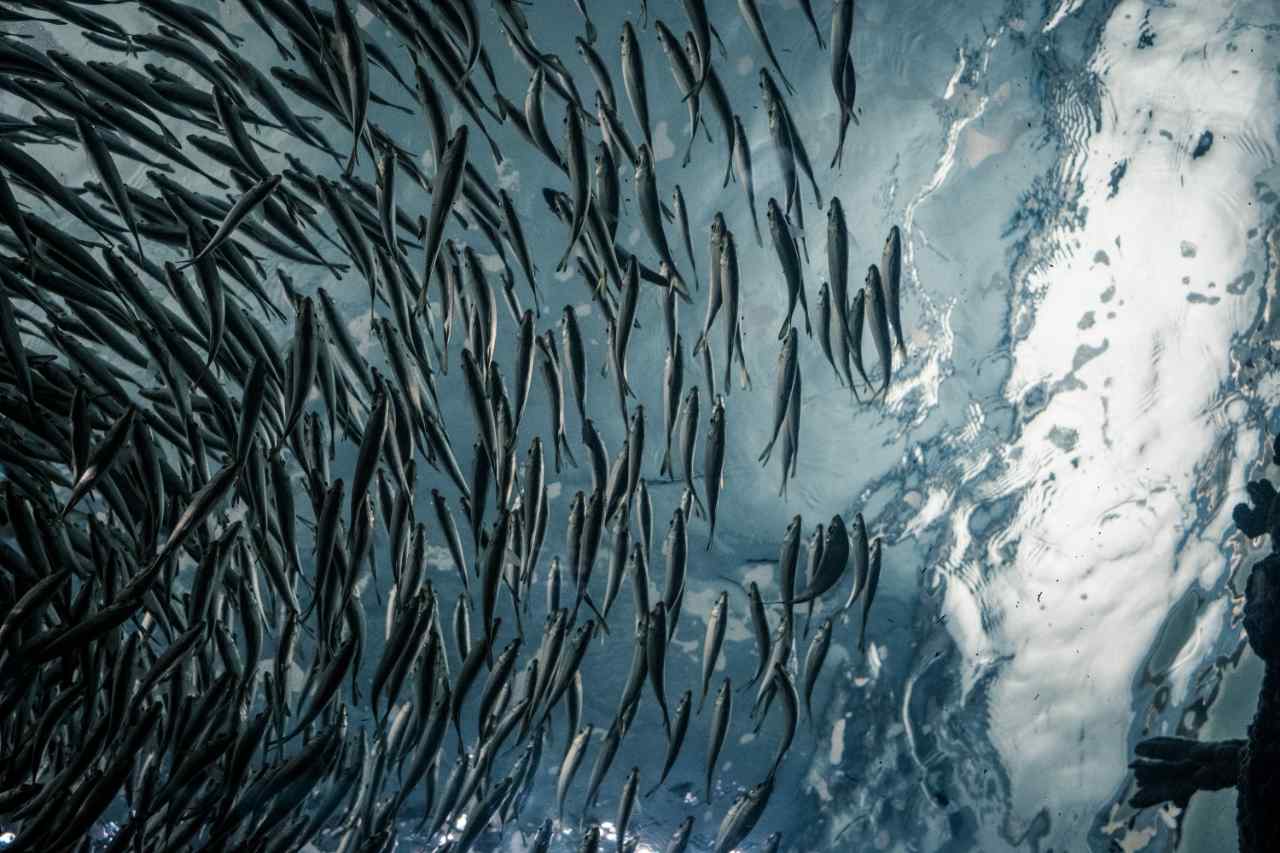

Image from Guilherme Bustamante on Unsplash

A small organization looks to unlock systemic change

NOS is a small organization, but it realized that if they looked at this problem systemically, they could potentially change the dynamics. Liliana describes NOS’s mission as, “awakening the desire of communities to produce change, to produce transformation, and then help them to acquire the necessary tools to change their system and produce different results than the ones they have right now.”

Their work in the community began with a multi-stakeholder collaboration network. Although relations were strained, NOS quickly found building connections with the local children and women provided an authentic lens through which to better understand the community.

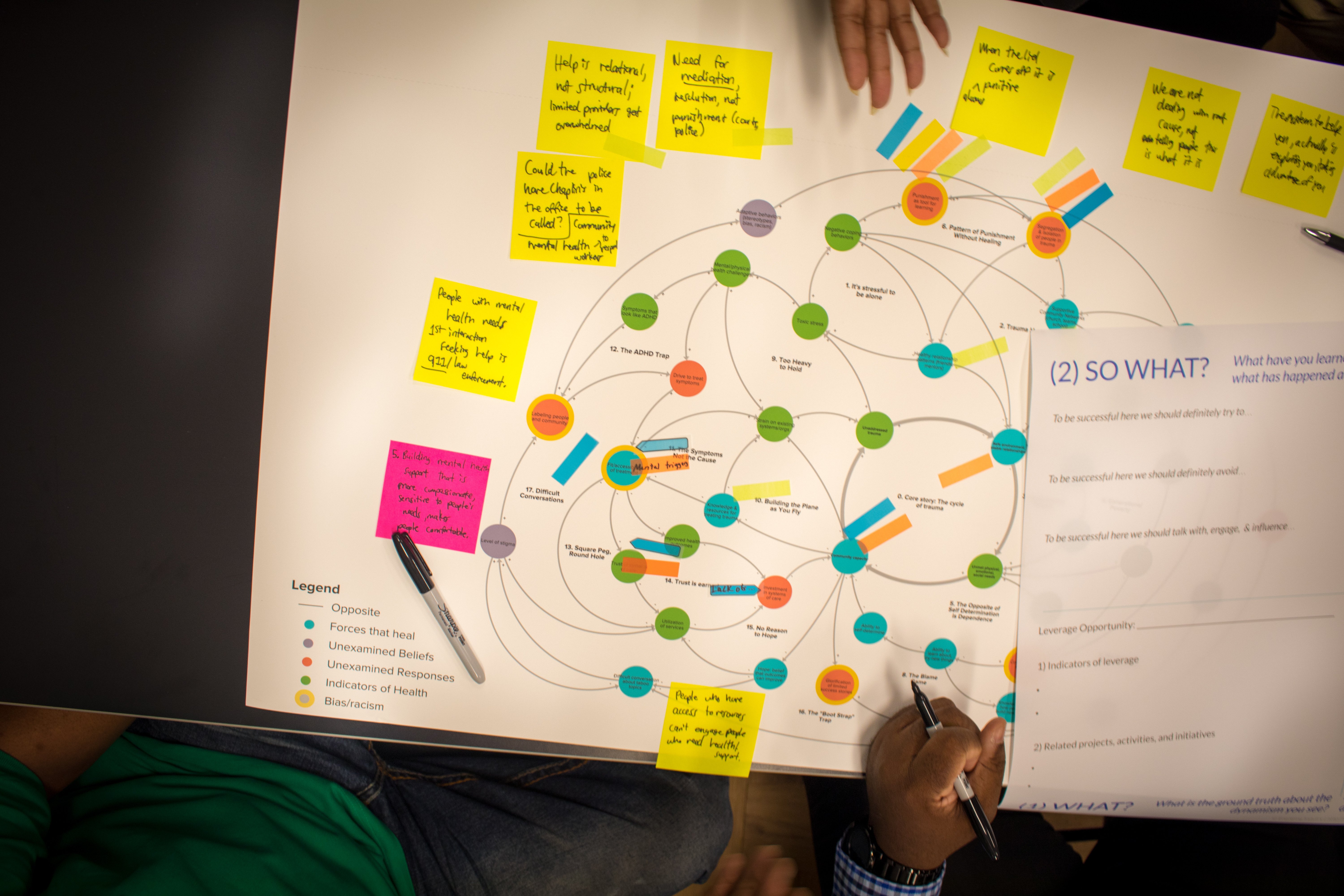

They started to try to map the forces and dynamics that were at play to better understand the community--but they didn’t get it right at first. Liliana recalls: “I still remember the first time that we shared systemic maps with the community and how weird it was. At the beginning, we would first draw the system and show it to the community and say, ‘Hey, this is your system. Now let's think about how to intervene.’ Then they were like, ‘What’s that? No, no, that's not me!’

"That's when we discovered that the system emerges as another guest in your circle, but you have to build it with them.”

Key mindsets for systems change

While there is a temptation to enter a system as an outsider and provide instructions to those involved to ‘fix’ their issues, Liliana realized this is the opposite of what environmental conservation needs in order to achieve lasting results.

Instead, she realized two critical things:

#1 - Systems change involves questioning hierarchies and realizing we can't accomplish things individually.

“We need to break the idea that leadership goes with one single individual. I love the concept of incomplete leadership - all of us are incomplete leaders. That's why we need to work as a team.

Nothing can be achieved by one single person no matter how smart, how brave you are, we actually are a tribe and we need to cherish that. And that's great because it means that we can complete ourselves by being together. We need to be more in circles. Because in circles there are no hierarchies; there are no differences. Circles are the base of a systemic approach.”

#2 - Silence is powerful. Systems change involves listening to perspectives beyond your own and using them to build a new collective understanding of a challenge.

“If you want to tackle the challenges of humanity using a systems approach, give yourself the gift of silence.

Our societies are so used to filling all the silence with noise; we're not used to silence, but it's only through silence that the new will emerge...it is only through silence that you actually learn to listen.”

Unlocking community desire to change the system

NOS began working with the community to uncover the possibilities for restoring the lagoon. Liliana describes how the desire for this change “was deep at the heart of the community,” and that, “we had only to listen when this fantastic community first stated a vision.”

It was the community who declared, “We want to be legal fishermen. We want to be the best fishermen in the world. Of course, we want to respect the law. Of course, we want another type of life and…we want another future for our children.”

With this acknowledgment, the fishermen began to see their system through new eyes. They started to think differently about the futures of their daughters and sons and realize it was important that they attend school so that they had more options for employment. They began to consider their health as individuals and the health of the community as a whole.

Liliana remembers an extraordinary moment when one community member said: “To restore Ensenada [the cove] first we need to restore ourselves.” This moment is a reminder that, at the most basic level, systems change starts with the willingness to change personally.

Re-envisioning roles and managing trade-offs

Ultimately, the community recognized that a healthier fish population would result in more economic opportunity. They decided they were willing to do what it would take to generate more wealth and wellbeing.

Liliana explains: “The fishermen and said: “You know, it's not that we don't want protected areas. We know we need to protect the ocean... If you help us to stop fishing pen shells, it’s going to take two years for the pen shell population to increase again to a level that we can fish.’ And that's when the journey began. Because they said, ‘Okay, let's stop fishing.’”

Although the community understood that temporarily halting their fishing practices would result in more prosperity in the long run, this decision didn’t come without challenges. Some fishermen moved into new jobs but most recognized there would be a period with less income as they worked towards restoring the marine environment.

Liliana encouraged the community to see how their expertise as fishermen might make them exactly the right people to restore the local environment--since they knew it best: “What if we see that the system that we have now is a result of all our past actions. Actually, we were so good at fishing that we depleted the resource. First we were fishermen, now we need to be restorers. We need to go and restore what we depleted.”

With NOS’s guidance, the fishermen realized they had the skills needed to take on this new conservation role and restore both their fisheries and the community’s prosperity.

Identifying the most powerful leverage points: Jobs and education

With the community’s interest in conservation now solidified, the conversation moved to economic sustainability for the fishermen. How would they be compensated for their new roles as aquaculture specialists restoring the local habitat?

NOS realized they needed to convince philanthropic foundations to use their grant dollars to fund these conservation jobs and compensate fishermen for their new role restoring the ocean. For some foundations with a mission to conserve the environment, it was a radical idea to think about paying people who had previously been illegal fishermen. But NOS successfully convinced them to invest in this type of systems change. Liliana explained that providing jobs to fishermen was actually a key leverage point to change the larger dynamics of the problem.

As Liliana summarizes, NOS worked to, “prove the direct connection of paying fisherman with conservation or restoration results. We had to prove that by paying fishermen to restore, the fishery was going to grow. Accordingly, we would therefore create capital that would then be enough to pay the fisherman and eventually phase out the philanthropic money.”

Additionally, a community fund was also established to help families afford education costs while the fisheries were being restored. The scholarships have already helped two women graduate from college - one as a marine biologist and one as a psychologist.

Working towards a more sustainable future

The work that NOS and the fishing community did in El Manglito has been more successful than anyone imagined at the outset. Community members engaged with scientists to learn about restoration and population management. They took the knowledge, formed a 109 member cooperative, and formally asked the government for rights of their fishery.

Liliana shares, “This is the only community that we know of, that has proven that a fishery can be restored to self-organization of a community with a systems view and then be acknowledged formally by the government to manage it.” NOS’s vision is eventually to convince the Mexican government that all the money they currently spend on fishing subsidies can be used instead to create the jobs needed for restoration.

By the time NOS had established themselves in El Manglito in 2012, the lagoon’s pen shell clam population had plummeted below 66,000. With the help of NOS’s systemic approach and the community’s commitment to conservation and restoration, the pen shell population has climbed to more than four million.

The community-owned fishery now provides income for 100 families, and El Manglito residents have reclaimed their agency to be smart stewards of their resources and livelihoods.

To learn more about this initiative, the Academy for Systems Change has written extensively about NOS and El Manglito’s journey to sustainability.

The residents describe their experience restoring the bay in this short video:

Close

Author

Danielle Sutton

Danielle Sutton is the Content Animator at Acumen where she surfaces stories to inspire and activate social entrepreneurs. In an age of information overload, she believes in learning 'the right thing at the right time' to intentionally design impactful social enterprises. You can usually find Danielle digging into the Acumen course library, playing in the mountains, or exploring marketing on The Sedge blog.