Leadership

Disrupting the cycle of gender-based violence in rural India

Mathangi Swaminathan, Founder of Parity Lab, shares how to unlock the funding needed to shift systemic violence

August 23, 2023

1 in 3 women face violence in their lifetime. That’s over 1 billion people around the world. In India, every hour, at least two women are sexually assaulted and every six hours, a young married woman is beaten to death, burned, or driven to suicide.

Mathangi Swaminathan is working to change that. She is the Founder of Parity Lab, a groundbreaking initiative supporting survivor-led grassroots organizations that address gender-based violence in rural India. Through an 18-month accelerator program, Parity Lab provides these organizations with capacity building, access to funding, and mental health and legal counseling support.

The goal: to strengthen their ability to help marginalized women survivors heal and seek the justice they deserve.

Through her work, Mathangi has gathered notable achievements as a 2017 Acumen India Fellow, an Acumen Angels recipient, a 2023 Echoing Green Fellow, a World Economic Forum Global Shaper, and winner at UC Berkeley’s Big Ideas Contest.

Yet, as a minority immigrant woman of color, Mathangi also faces fundraising challenges not unlike the grassroots organizations she supports.

From both perspectives –– as a mentor and through her own lived experiences with these challenges –– Mathangi discusses the difficulties of fundraising and shares how we can all contribute to disrupting the misconceptions of gender-based violence and support a cause affecting thousands of Indian women, and millions around the world.

Systemic violence: The missing story about gender-based violence

Mathangi launched Parity Lab during the COVID-19 pandemic when she noticed two concerning trends: first, a surge in domestic violence cases worldwide, with India experiencing a drastic increase in girl child marriages (60-70%); and second, political changes in India which led to a decline in international funding for grassroots organizations.

“I remember really feeling helpless. I kept hearing reports from grassroots organizations calling me up and saying, ‘Violence has massively increased, we don't know what to do. [We don’t have enough funding], we might be shut down.’”

Feeling compelled to take action, Mathangi founded Parity Lab as a support system for survivors leading change by fighting gender-based violence. Parity Lab recently released a white paper mapping the journey to justice for rural Indian women. Through interviews, case studies, and focus groups, the research reveals a crucial aspect of gender-based violence that is grossly overlooked — systemic violence.

While we commonly associate gender-based violence with intimate partner issues within heterosexual relationships, there exists an untold story about the systemic violence that plagues survivors and prevents them from seeking the justice they deserve.

A police force contributing to systemic violence

One shocking example of this systemic violence is how gender-based violence cases are often handled by Indian police. 40% of officers say most complaints are unfounded, leaving countless women in rural India struggling to be heard. Grassroots organizations often spend days, weeks, or even months protesting for a case to be filed in the police system.

There's a misconception that legal remedies can easily resolve gender-based violence, assuming women merely need to come forward and go to court. But the reality is vastly different. India's legal system is notoriously slow, often taking more than a decade to deliver justice, even for affluent women with connections.

Now imagine the plight of a rural woman in India — someone who's likely uneducated, raising several kids, and lacks the means to travel to court. The hurdles she faces are almost insurmountable.

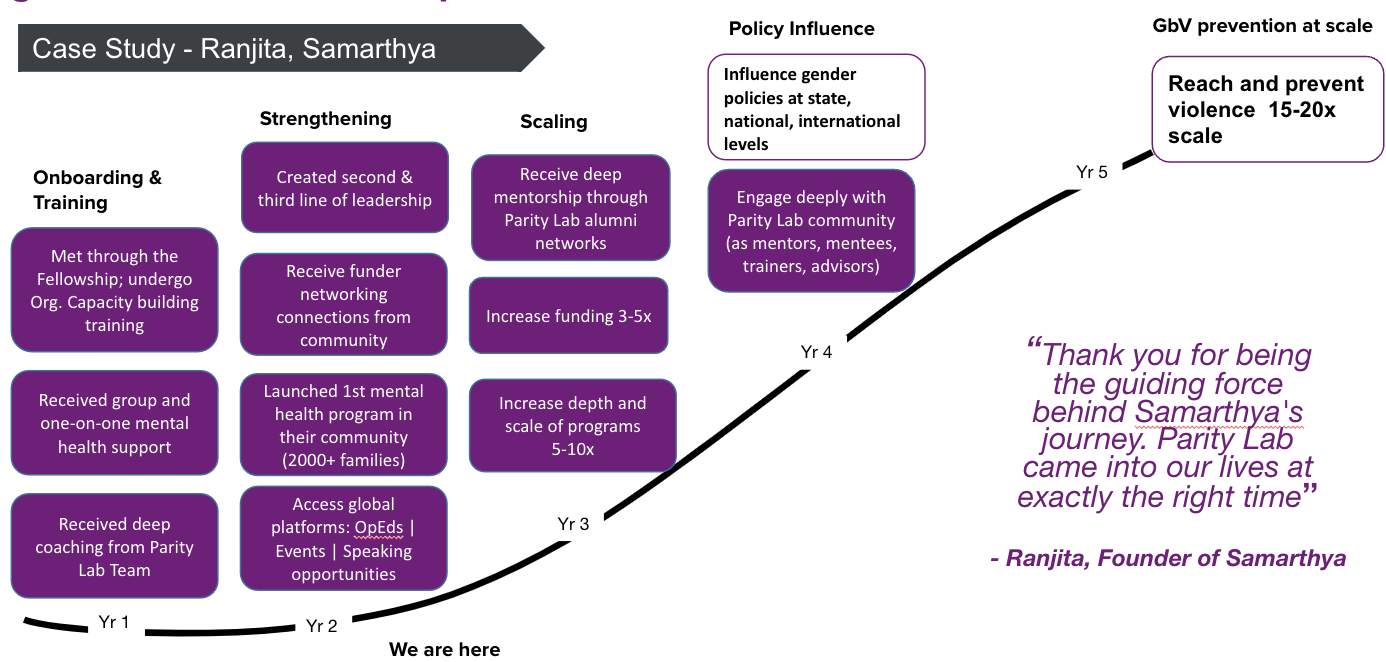

Case Study

The unjust journey towards justice for India's Denotified Nomadic Tribes

Ranjita Pawar is an Indian woman from the Denotified Nomadic Tribes in rural Maharashtra and the Founder of Samarthya, a youth and Indigenous women-led organization. Her tribe has been marginalized and stigmatized since the British colonial era. This legacy of criminalization persists in modern times, as they are disproportionately represented in prisons and face relentless police violence.

From a young age, Ranjita bore witness to the often misdirected violence inflicted on her community. Her organization supports women victims of gender-based violence and also works on engaging men and boys to change gender norms. But seeking justice is an uphill battle riddled with systemic challenges.

Ranjita’s tribe exists at the intersection of three different states in India, creating a labyrinth of bureaucratic complexities. If the crime involves a woman married across state lines, authorities often dismiss her pleas, citing jurisdictional issues.

"You must travel 60 kilometers to the other jurisdiction and figure it out," they say, adding another layer of hardship to an already arduous journey."

Once the woman finally makes her way to that station, she often finds the police officer is unavailable. It can take days before she even makes contact with an officer.

Mathangi explains, “When these interstate jurisdictions come into play, all of a sudden their rights also mean something very different. Often, legal solutions that are available in urban areas do not exist for rural women in these nomadic tribes.”

In this intricate web of injustice, the Denotified Nomadic Tribes face unique challenges. In many cases, there might not be a police presence, leaving their case in the hands of village councils known as panchayats. These councils, predominantly comprised of upper-caste men, wield the power to decide cases of sexual assault and rape.

When all of these systemic challenges — lack of education, literacy, poverty, geography, male dominance — intersect, legal counseling, mental health, and justice look very different from what the outside world would imagine.

Above: Theory of change model for Ranjita's organization, Samarthya.

Family contributions to systemic violence

Victims also face systemic challenges within their own family. One such challenge is the concept of "compromise," a distressing practice where parents and in-laws exchange money and goods without the survivor's consent in order to preserve family integrity, preventing cases from reaching the authorities or drawing attention from grassroots organizations.

Meena Devi is the Founder of SSK Lalitpur and a grassroots leader working with Mathangi. She has encountered over 200 cases where this notion of “compromise” has taken place, sometimes after the woman has been severely sexually assaulted or has died as a result of the violence.

Mathangi says organizations like Meena’s “come across extreme forms of societal systemic violence and injustice against survivors that are sometimes even worse than the interpersonal violence they’ve faced.”

Parity Lab brings to the forefront the voices and untold stories of women who have experienced these systemic challenges, all of which compound to create seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Without the essential support provided by grassroots organizations, these vulnerable individuals would be left without anyone to champion their cause.

“These organizations are the only front lines. How can we position them as experts in this field — acknowledging their work as research, novel, and worthy of attention? Positioning them as experts and listening to their on-the-ground experiences can lead to a fundamental shift in how we discuss and address gender-based violence.”

You can help change the narrative by drawing awareness. Share this story.

Change happens when we break down barriers

The cohorts that participate in Party Lab’s accelerator programs are all Dalit, Indigenous, Nomadic Tribal women serving over 2,000 families in their region for the past 10 to 15 years. While these women are skilled community organizers, they face challenges in defining organizational structures, capacity building, fundraising, and providing mental health and legal counseling to the women they serve.

“So that’s where we come in. And much of our impact is very direct,” Mathangi shares.

Within a year of the accelerator fellowship, Parity Lab witnessed a fourfold increase in fundraising efforts for the grassroots organizations. They’ve helped these organizations define structures, identify outcomes, improve relations with funders, and establish second and third lines of leadership.

Parity Lab recognized the need for mental health support among these organizations due to the trauma involved in their work. As a result, they introduced formal mental health concepts, and now two out of three organizations have implemented mental health programs for their communities.

“We have seen this waterfall effect. They get so excited to learn and share what they’re experiencing. That's the effect of empowering leaders of change. If it goes right, it spreads.”

However, one significant challenge is providing legal counseling within a broken system.

“There is this dichotomy of feeling empowered knowing your rights, yet disempowered knowing there’s actually no use in knowing your rights. What do you do with that? This is a question our cohort leaders face day in and day out.”

Parity Lab is exploring ways to offer practical and aspirational legal counseling by leveraging early-stage funding from Acumen Angels to support grassroots leaders addressing this issue.

“Hopefully by building out this ecosystem we can make a difference to the system. But it’s about starting at a very small level, supporting our grassroots leaders who are taking on these practical challenges.”

Systemic challenges of fundraising for gender-based violence

But similar to the grassroots organizations she supports, Mathangi faces systemic challenges when fundraising for Parity Lab. Limited funding for gender equity and violence initiatives results in gatekeeping and power brokering, making it hard to access resources.

“Even during the peak of COVID-19, when gender-based violence became a shadow pandemic, only 0.0002% of nearly 27 trillion dollars in donor funding went to initiatives addressing it.”

This creates a situation where everyone is competing for a small pool of funding, despite the fact that this issue affects over 1 billion survivors worldwide.

Another challenge in fundraising is the misunderstanding of gender-based violence. It's not just about providing legal aid, but requires addressing complex root causes through systemic change. As Mathangi explains, “Often funders want a linear solution, ‘Do X, and that leads to Y.’ But that rarely happens. This is a big misunderstanding we’re up against.”

Three ways to change the narrative of gender-based violence

Mathangi proposes three ways to improve the funding landscape, emphasizing the importance of supporting early-stage entrepreneurs who are addressing gender-based violence.

1. Centering on the needs of grassroots organizations

Mathangi points out a discrepancy between funding institutions' language about "grassroots" and the complex, resource-demanding application processes that deter small grassroots organizations.

To align with her beliefs, Mathangi implemented a grassroots-focused application process for Parity Lab's accelerator program, in order to make the process truly accessible to grassroots and women survivors from marginalized communities.

The application is simplified to two questions and is available in multiple languages to accommodate diverse applicants. It focuses on applicants' dedication to gender-based violence rather than their formal education, assessing their skills via community engagement and background checks. This approach reflects Parity Lab’s core values and commitment to focus on the needs of their target community.

2. Women funders as funding catalysts

Mathangi believes women funders are an incredibly important part of the ecosystem, noting that the first three funders she secured were women-led foundations and transformative contributors: “They can be some of the most catalyzing funders in this ecosystem. I think women haven't often recognized how powerful they can be.”

As those most affected by the issue, women possess a unique understanding and a deep emotional connection. This innate understanding enables them to drive change effectively, particularly concerning funding.

Know a female funder who could help catalyze change? Share this story.

3. Breaking the cycle of “like attracts like”

Mathangi emphasizes the significance of introductions. Institutions typically require connections for funding applications, limiting access to well-connected individuals and organizations.

“Many of the people who have touched me in the last 2 years have said, ‘Oh, you know, I can make this introduction for you to this network’ — which I'd never heard of, but apparently has a lot of funding opportunities.”

She’s noticed that funding opportunities often remain confined within specific bubbles. Unless you're part of a racial group, affinity group, university group, or you have an affiliation towards that specific issue or group, it’s hard for an opportunity to make its way to a broader audience.

Let’s disrupt the system

Mathangi urges us to disrupt existing systems and promote cross-pollination between different networks. Diversifying representation in the gender-based violence space can ensure that funding and other opportunities reach those on the ground, doing the work.

Mathangi reminds us that change can start with small actions. By disrupting the cycle of gender-based violence misconceptions and shedding light on the realities facing women victims, we can begin to dismantle the broken and harmful systems that prevent millions of women around the world from seeking justice.